- Editor

- Posted On

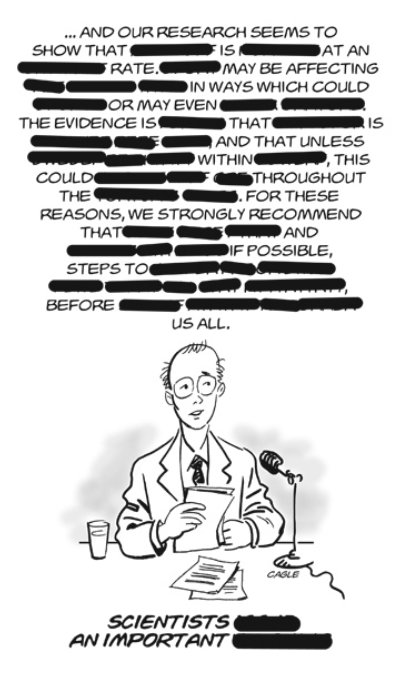

The censorship of science undermines democracy

At a major congressional hearing in January, a prominent NASA climatologist spoke publicly about attempts by agency officials to interfere with his ability to release his research results that described impact of global warming on Antarctica.

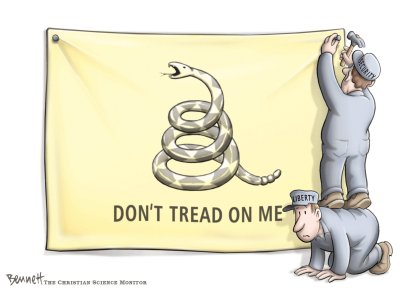

Sadly, the scientist is not alone. Growing evidence shows that over the past several years, political interference in federal government science has become both widespread and pervasive. To ensure that science – one of the cornerstones of American democracy – continues to serve society, public officials must act to defend taxpayer-funded science from political interference.

The Bush administration has censored scientists, suppressed reports, and altered scientific documents on issues ranging from mercury pollution to childhood lead poisoning to drug safety. And for every scientist who is able to speak out against political interference in his or her work, scores of others have been pressured into silence and don’t have the standing that would allow them to speak without retribution.

Recent surveys by the Union of Concerned Scientists found that nearly 40 percent (699) of more than 1,800 scientists working at nine federal agencies report that they fear retaliation for openly expressing concerns about their agency's work. In a survey of climate scientists alone, 150 scientists reported at least 456 instances of political interference in their research or the communication of their results. These numbers should be zero.

Just as troubling are actions that politicize science by limiting public access to information and hindering public oversight. In its second term, the administration has closed federal scientific libraries that housed unique documents. It significantly reduced the public’s right to know about the chemicals factories release into our neighborhoods. And new administrative procedures effectively keep science out of many critical decisions.

Take, for example, the air we breathe. Environmental Protection Agency staff scientists have worked for decades with an independent scientific advisory committee to review the best available science on air pollutants and recommend appropriate pollution control standards. Last year, when the committee scientists objected to an EPA decision to set soot pollution standards that twisted the science and failed to protect public health, the agency responded with a new policy that significantly limits scientific input into the process.

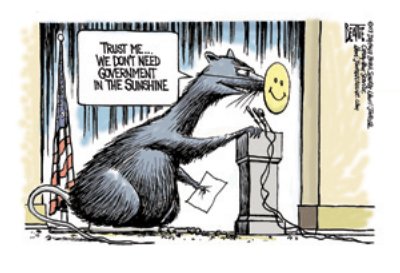

In a more recent example, President Bush’s January amendments to an existing executive order could further centralize regulatory decision-making power in the White House. The new rules place political appointees deeper inside federal scientific agencies where they can more easily prevent scientific data from ever seeing the light of day.

In response, nearly 12,000 scientists, including 52 Nobel laureates and science advisers to both Republican and Democratic presidents dating back 50 years, signed a statement condemning this abuse and calling for reform. "The distortion of scientific knowledge for partisan political ends must cease," they said, "if the public is to be properly informed about issues central to its well being, and the nation is to benefit fully from its heavy investment in scientific research and education."

Indeed, our nation’s prosperity is based on a foundation of independent, unfettered scientific discovery. Decision-makers must have access to the best available scientific information to make fully informed decisions that affect public health and the environment.

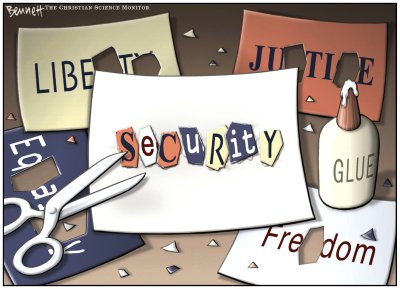

It’s time for action. There are no laws that protect federal scientists from retaliation for truthfully and publicly reporting their scientific results. Congress should act quickly to pass strong whistleblower protections for federal scientists who report scientific abuse.

Restoring scientific integrity to federal policy making will also take the persistent and energetic engagement of the next president. Presidential candidates should promise a zero tolerance policy for the manipulation and suppression of taxpayer-funded science. Candidates must commit to a philosophy of open government that allows scientists to speak freely about their scientific research and enables science to effectively inform public policy.

This is not an abstract debate. In the coming year, the administration will be faced with a number of critical science-based decisions. The EPA will set standards for pollution from lead and ozone. The Food and Drug Administration will continue to determine the safety of new prescription drugs and medical devices. And the Occupational Safety and Health Administration will debate regulations that protect the health and safety of workers.

Scientific freedom – the ability of scientists to conduct research and share their results free from government interference or censorship – is vital to a democracy. The thousands of scientists employed by the federal government represent a tremendous resource. Without a culture of scientific independence, public understanding of scientific issues will suffer, and our public officials will be unable to meet America’s most pressing challenges.

Francesca Grifo is a senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists and director of the UCS Scientific Integrity Program in Washington.

{mos_sb_discuss:2}

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?