LAKE COUNTY, Calif. — California hasn’t lost a species in 50 years, but that could soon change if efforts to save the Clear Lake hitch fail.

The population of the hitch, a large minnow native to Clear Lake and its tributaries, is crashing, local tribes are asking state and federal agencies for immediate intervention and on Thursday the state held a virtual meeting with Lake County residents and officials to discuss the emergency.

The hitch’s troubles began decades ago. Once reported to number in the millions, over the last decade, the hitch population has plummeted.

In 2014, as the situation was accelerating, the hitch was listed as a threatened species under the California Endangered Species Act. However, the federal government hasn’t followed suit so far.

The hitch has traditionally been a primary food source for Lake County’s Pomo tribes. In December, those tribes and the Center for Biological Diversity asked the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to provide emergency protections to the fish. They also held a summit with state and federal agencies to discuss immediate help for the hitch.

Concerns about the hitch led to the proposal for a proclamation of a local emergency by the Board of Supervisors at the Jan. 10 meeting, but that discussion was rescheduled to Jan. 24.

On Thursday, the State Water Resources Control Board held the first of two public listening sessions about the hitch.

Thursday’s State Water board session started out with some technical issues with its Zoom link. Officials said they have updated the links to avoid that problem at the Feb. 1 session.

Valerie Zimmer of the State Water Board said there is widespread agreement that the hitch has been in decline for a long time.

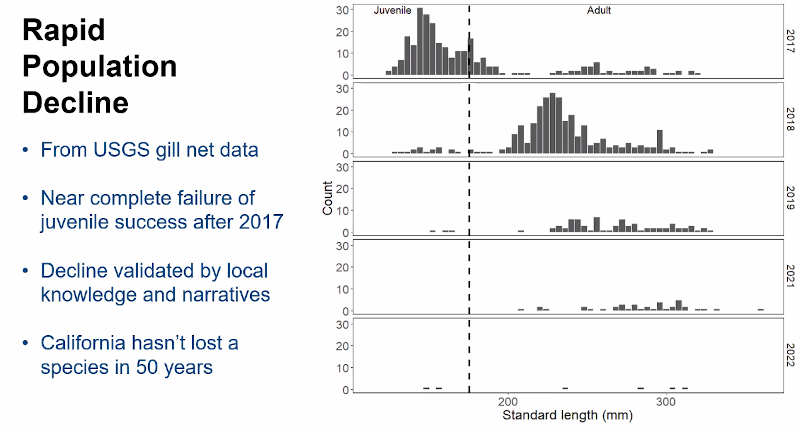

She showed a graph of hitch population and juvenile spawning data collected by the United States Geological Survey.

The data showed that there has been a near complete failure of juvenile hitch success after 2017, with Zimmer noting that the decline is validated by local knowledge and narratives.

The slide showed that a small number of juveniles were recorded in 2018, a smaller number in 2019. There were no numbers given for 2020, and then in 2021 no juveniles were recorded. In 2022, only a very small number were found.

“This looks like the population is crashing right now,” she said.

With the hitch having up to a six-year life cycle, if they don’t come back this year, Zimmer said they may be gone for good.

“Unfortunately we are late to this issue,” Zimmer said, adding that the state is catching up and working with local agencies and organizations.

As for why the hitch population is crashing now, Zimmer said there is no single cause and no single person who is responsible, although the drought is having an impact.

Zimmer said the hitch’s peril is due to human activity. Examples of harmful activities include:

• Flow barriers: Culverts, stream bed alterations and dams.

• Insufficient water flow volumes: Drought impacts, surface diversions and losing streams.

• Habitat degradation: Mining, land use changes, levee development and flood control.

• Predation and competition with invasive species

• Pollution: Mercury and harmful algal blooms.

Flow barriers may be a critical issue as hitch don’t jump over barriers. Zimmer said they can migrate when there is a lot of water, but not when water is low.

A key issue is lack of flow in Lake County’s creeks. “If there’s no water in the creeks, none of this other stuff matters,” Zimmer said.

Zimmer also showed a picture of a 2014 fish kill in Adobe Creek, when juvenile hitch got stuck and died. Just a week before, the creek was running very high, so a biologist couldn't get into the creek to get the fish out.

More recently, Lake County’s tribes have carried out successful fish rescues, such as one that occurred in April when Robinson Rancheria and Habematolel Pomo tribal members worked with the Lake County Water Resources staff and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to rescue hundreds of hitch from an isolated pool in Adobe Creek near Soda Bay in Lakeport.

Other possible factors impacting the hitch’s numbers include illegal water diversions, cannabis, turning in pumps too early, overallocated water and groundwater use, especially when wells are close to creeks. Zimmer acknowledged data gaps and a lot that isn’t known.

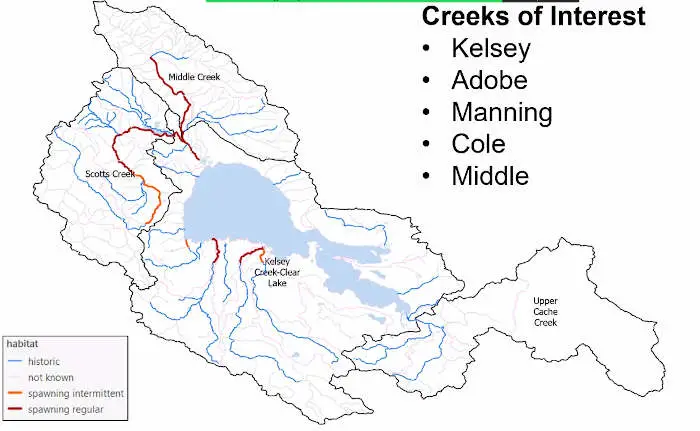

Zimmer said the focus is being placed on the creeks that historically have had a lot of hitch in them — Adobe, Cole, Kelsey, Manning and Middle creeks.

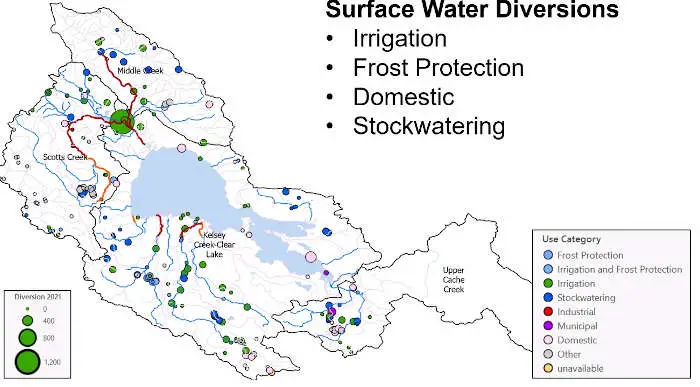

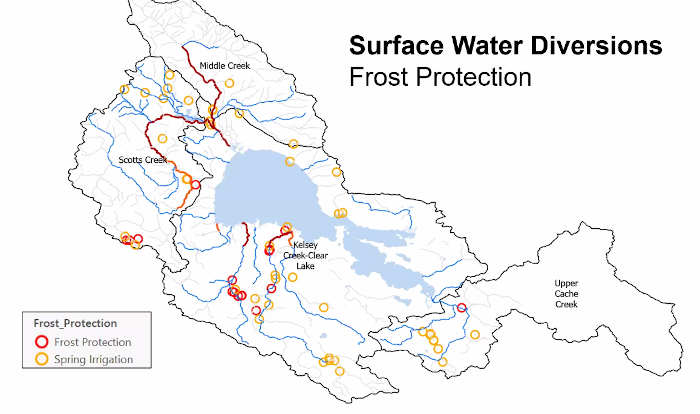

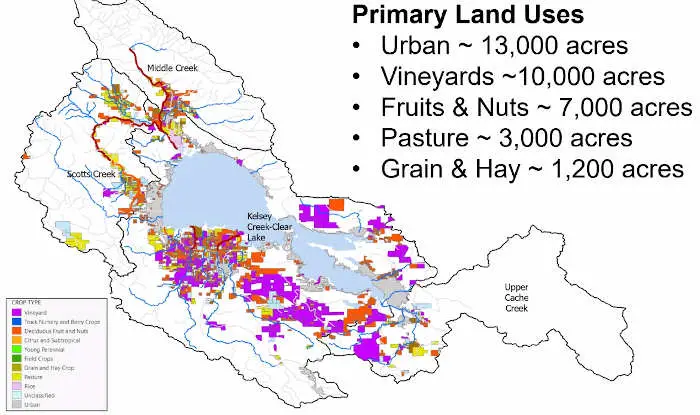

She showed maps of surface water diversions — irrigation, frost protection, domestic water and stock watering — as well as a map of uses like frost protection, which tends to occur in the spring when the hitch are migrating.

Primary uses for water in Lake County include urban, 13,000 acres; vineyards, 10,000 acres; fruits and nuts, 7,000 acres; pasture, 3,000 acres; and grain and hay, 1,200 acres.

Zimmer said the state is not looking at the entire county as it tries to address the situation. “We’re focusing on the areas that are important to the hitch.”

“I do think agriculture can be a really strong partner,” said Zimmer, explaining that some farmers are offering to put water into the creeks to get them moving so the fish can survive.

She said farmers also can help by looking for barriers — including roads and structures — on their properties that may impact the creeks.

John Murphy, a senior engineering geologist in the State Water Resources Control Board enforcement division, discussed the effort to get regulations in place, which can’t be done within just a few months, and takes time and data.

“At the end of the day, we know that the hitch is in trouble,” and the state wants to do everything they can to protect the fish, he said.

Murphy went over voluntary actions to keep water in the creeks this year, such as reductions in diversions and pumping, coordinating diversion and pumping timing, alternating frost protection methods and pump banks — using groundwater for streamflow. He said they are open to suggestions.

He said they have research going back to the 1950s when the hitch started having trouble.

There are concerns that, even with all of this year’s rains, the storm that took place on Wednesday could be the last rain for months, following a pattern from last year.

Murphy said they have information and momentum to help the fish. “We can’t lose this momentum. We don’t want the hitch going extinct on our watch.”

He said they are early in effort with lots of questions and possible solutions. Murphy added that they can’t let uncertainty about what actions to take lead to the hitch’s extinction.

As for what’s needed from the community, State Water Board staff said they need commitments for specific voluntary actions, such as reducing diversions and pumping from February to May, using alternative frost protection methods, coordinating diversion and pump timing.

They’re also looking for local coordinators, people to share data, leads on connecting with hard-to-reach people and invites to community meetings.

The state wants to hear what people would do to solve the problem in the short and long term, and get input on what specific steps the public thinks it should take.

There will be additional engagement opportunities with the state coming up.

The hitch will be discussed at the Board of Supervisors’ next meeting on Tuesday, Jan. 24, and the State Water Board will hold another listening session from 6 to 8 p.m. Wednesday, Feb. 1, via Zoom, http://bit.ly/CLH_Feb.1.

For more information, visit the State Water Board’s Hitch webpage. To receive email updates, email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Email Elizabeth Larson at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Follow her on Twitter, @ERLarson, or Lake County News, @LakeCoNews.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?