I had just turned 13 when I learned that the government in my native country of Cuba had imprisoned more than 15,000 men and women for political reasons. The majority of them were in jail because of their ideas. Others were detained for "conspiracy against the government," and many more for attempting to leave the island, which at that time – as now – was considered treason.

I did not hear the truth about the prisoners through the government's disclosure or from the Cuban press. I learned about it in May of 1977, because in the midst of political overtures to President Jimmy Carter, Fidel Castro decided to offer an interview to American journalist Barbara Walters.

To the surprise of Cuban people accustomed to covert behavior by their government, the interview was broadcast. "What about the political prisoners?" Walters asked. This single inquiry – something I had never before heard asked in Cuba – alerted me to the importance of asking questions that demand precise answers from our leaders.

Walters' pointed question had such a strong impact on me that it sparked my passion to become a journalist. Twenty years after starting my career at The Miami Herald, that passion still guides my pen and my career choices.

On several occasions, I have attempted to return to Cuba to report stories. For example, in 1999 I applied for a visa to interview Cuban government officials about racial conflicts on the island. My visa was denied. The Cuban authorities in Washington D.C said there were no racial issues on the island.

In 2003, I asked for permission to travel to Havana to research information for my book about the 1980 Mariel boatlift, when more than 125,000 Cubans left the island within a five-month period. I was refused again. This time, I was told that the topic was not of interest to Cubans. Even so, my book, "Finding Mañana: A Memoir of a Cuban Exodus," was published. It was well received by literary critics and readers alike despite the Cuban government's refusal to tell its side of the story.

Where I work now, teaching journalism at Columbia University's Graduate School of Journalism, there is a sign at the entrance hall that I often read in the mornings. It is a quote from Joseph Pulitzer, founder of the School of Journalism. It says: "Our Republic and its press will rise or fall together. An able, disinterested, public-spirited press, with trained intelligence to know the right and courage to do it, can preserve that public virtue without which popular government is a sham and a mockery."

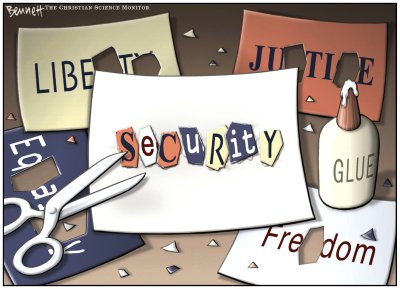

In these uncertain times when governments – including the U.S. government – persistently obscure the facts, Pulitzer's statement echoes even louder.

The public has the need to understand; indeed, the right to know, how their elected leaders exercise the powers vested in government by the electorate. Citizens expect their leaders to treat their power with humility and a sense of mission, to honor the voter's confidence, not to abuse it.

Transparent governments empower and educate their electorate, essential elements for true democracy to function and flourish.

Mirta Ojito is an author and professor at the Graduate School of Journalism, Columbia University, New York.