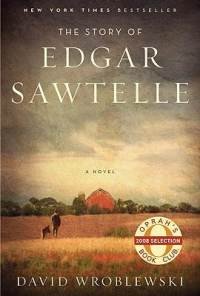

The Story of Edgar Sawtelle

A novel by David Wroblewski

Published 2008 by HarperCollins ISBN: 978-0-06-176806-04

The story is set in rural Wisconsin, on a remote farm where the Sawtelle family raises a unique breed of dog.

Long before I was half-way through this masterful book, I found myself limiting my reading time in hope of making the journey last longer. My resolve eroded at the end, as I was unable to put it down for the last hundred pages. Like a roller coaster cresting the top of a high loop, momentum built up to where putting on the breaks was no longer an option.

I did not know that books this good were still being written today. So much modern fiction is written according to the same rules, predictable as only the products of writers who have all taken the same writing courses and read the same writing manuals can be. And the ironic thing is, the plot of “Edgar Sawtelle” is totally predictable (to those versed in the classics). And yet, knowing the plot doesn’t tell you anything, really, about the book, which is full of unforeseen delights and “A-ha!” moments.

So, the first great tantalizing contradiction of “Edgar Sawtelle” is that it is one of the most familiar plots in the history of literary fiction, and at the same time, an utterly original and surprising book.

Though it should not be pigeon-holed (it transcends genre), it is also one of the greatest dog stories I’ve read.

My shelves are full of dog stories that I cherish – “Beautiful Joe,” “Bob Son of Battle,” “Lassie Come-Home,” “Big Red,” “The Voice of Bugle Ann,” “Old Yeller,” “Where the Red Fern Grows,” “Savage Sam,” “The Way of a Dog” and many collections of dog stories. Each celebrates the bond between humans and canines, but regard the bond as a mystery, never to be fully understood.

“Edgar Sawtelle” addresses the human-canine relationship in terms of the evolution of consciousness that both humans and canines have undergone, over millennia of evolving together. Canis lupus became different because they joined forces, so long ago, with another “pack animal,” Homo sapiens. And Homo sapiens are different because we joined forces, so long ago, with Canis lupus. Both species’ evolution was changed by the fact that we have evolved together. We're co-dependent species.

In the famous novelette “Childhood's End,” Arthur C. Clarke explored the evolution of human consciousness. In “Edgar Sawtelle,” the author makes a convincing case that human and canine consciousness are evolving together, destination unknown, but intertwined.

Though it is not necessary to know the play to appreciate this book, it is impossible for any fan of Shakespeare to fail to notice that the plot is from the play “Hamlet.” Nonetheless, “Edgar Sawtelle” stands triumphantly on its own two feet. Or rather, two feet plus all the four-footeds who are equally compelling and fleshed-out characters.

Heretic though it might sound, I will say that I think “Edgar Sawtelle” is better than “Hamlet.” A story better told.

In “Edgar Sawtelle,” we see deeper into the souls of all the participants. Which does not mean to say that “Hamlet” does not achieve profundity (no play holds our imagination for centuries without good reason). No, it is not that “Hamlet” is not great. It is just that, in my opinion, “Edgar Sawtelle” is greater.

I don’t recall any production of “Hamlet,” which made me feel such empathy and understanding for the other characters in that drama – the people whose lives, loves, feelings and world views were shaded into second-class citizen status in Shakespeare’s play, as if they existed for the sole purpose of giving Hamlet something to bounce off of. (The modern play, “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead,” took minor characters from “Hamlet” and made them central in their own drama. But that play was more about celebrating its own cleverness than shedding light on the human condition.)

In “Edgar Sawtelle,” we do get to understand, to empathize, with all these other characters, two-legged and four-legged, and their richness of characterization makes the story fuller, more moving. They all have solid motives for everything they do, and with the exception of the bad guy, they all have good intentions.

(WARNING: If you don’t like to know plot points in advance, you may want to read “Edgar Sawtelle” first, then read the rest of this review.)

As much as I’ve enjoyed many different productions of “Hamlet” over the years, on stage and screen, there is a certain quality about the play that leads one, eventually, to yearn for it to be over. “Oh for Pete’s sake,” one finds oneself thinking, as yet another lengthy soliloquy begins, “Hurry up and kill each other – anything – just stop the whining.”

Where Hamlet can come off as self-obsessed and self-pitying, rudely indifferent to the suffering of others, “Edgar Sawtelle” is different, in ways that cannot be explained without giving away too much. Towards the end, I found myself hoping against hope that in this book, the author (who had stuck so faithfully to the plot of “Hamlet” throughout) would have allowed himself just one eensy-weensie-itty-bitty liberty, one teeny-weenie deviation from the plot of the original, and allow… no, I won’t say it.

The crowning achievement of this book (to me), was the reminder that we miss the forest for the trees when we focus too intently on what our five senses tell us. To be so focused is to deny the truth we all hold in our breasts – that there is more to reality than just what our conscious mind is capable of perceiving.

Like so many who take “the hero’s journey” (for you Joseph Campbell fans), Edgar is heated to white-hot temperatures in the crucible of emotional, spiritual and physical torment. By the book’s end, all spare flesh has been burned away. All confusion and doubt are gone.

Where before there was fog, anger, jealousy, confusion, doubt, incomprehension – a soul buffeted in a sea of emotional turmoil – what emerges from the crucible is, in the book’s phrase, “a hollow gourd” – a man-child who sees everything clearly at last. I was reminded of an analogy from Lakota spirituality, that the pure soul who can bridge the gap between the spirit world and our world is like a hollow bone – a tube through which The Light shines.

The very act of hoping that death will not come to the lead character is a denial of the deep spirituality of the book.

Therefore, ultimately, though I cried buckets, I also felt joy in the cathartic ending. Joy for the success of a tormented soul who, at last, saw everything clearly, and who took the right action. For a soul who was finally at peace, after flailing about in pain for so long.

Most of all, joy for the re-uniting of true soul-mates, spirit-lovers, who had been cruelly separated by human blindness and human faults. “You were lost,” she said, by way of greeting him. “I was lost,” he agrees. Several hundred pages of riveting literature are thus summarized in a few short words.

Tragic ending? or happy beginning?

“In the depths of your hopes and desires lies your silent knowledge of the beyond, and like seeds dreaming beneath the snow, your heart dreams of spring. Trust the dreams, for in them is hidden the gate to eternity.”

So wrote Kahlil Gibran, centuries ago. It would make a fitting epitaph for “Edgar Sawtelle.”

D. Baumann lives in Upper Lake with many shunkas (dogs) and ta’shunkas (“Big Dogs,” Lakota word for horses).

{mos_sb_discuss:5}