Summer is mosquito season, and a new study gives insight into why repellents work on mosquitoes.

Spray yourself with DEET, and you’ll repel mosquitoes, but why? It’s not because DEET jams their sense of smell; it’s because they dislike the smell of the chemical repellent intensely, researchers at the University of California, Davis have discovered in groundbreaking research published Monday.

“We found that mosquitoes can smell DEET and they stay away from it,” said noted chemical ecologist Walter Leal, professor of entomology at UC Davis. “DEET doesn’t mask the smell of the host or jam the insect’s senses. Mosquitoes don’t like it because it smells bad to them.”

The study's conclusions about how the repellent works is especially important in a time when West Nile Virus has reached California. The disease has so far affected 92 people in 13 California counties this summer, according to the state's West Nile Virus Web site.

DEET’s mode of action or how it works has puzzled scientists for more than 50 years.

The chemical insect repellent, developed by scientists at the U.S. Department of Agriculture and patented by the U.S. Army in 1946, is considered the “gold standard” of insect repellents worldwide. Worldwide, more than 200 million use DEET to ward off vectorborne diseases.

Scientists long surmised that DEET masks the smell of the host, or jams or corrupts the insect’s senses, interfering with its ability to locate a host. Mosquitoes and other blood-feeding insects find their hosts by body heat, skin odors, carbon dioxide (breath) or visual stimuli. Females need a blood meal to develop their eggs.

Entomologist James “Jim” Miller of Michigan State University praised the work as correcting “long-standing erroneous dogma.”

"For decades we were told that DEET warded off mosquito bites because it blocked insect response to lactic acid from the host – the key stimulus for blood-feeding,” said Miller. “Dr. Leal and co-workers escaped the key stimulus over-simplification to show that mosquito responses – like our own – result from a balancing of various positive and negative factors, all impinging on a tiny brain more capable than most people think of sophisticated decision-making.”

He said the work also shows that a recent study on DEET published in the flagship journal, Science, “apparently was flat-out wrong,” Miller said.

“One of the great attributes of science is that, over time, it is self-correcting,” he added.

Leal said previous findings of other scientists showed a “false positive” resulting from the experimental design.

The UC Davis work, “Mosquitoes Smell and Avoid the Insect repellent DEET,” is published in the Aug. 18 edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

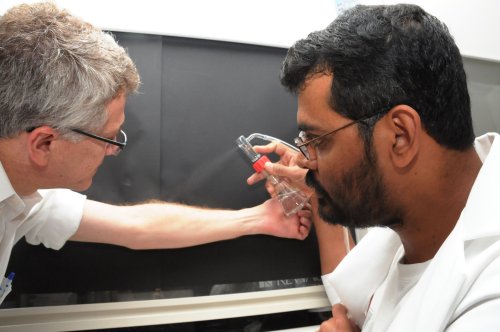

Mosquitoes detect DEET and other smells with their antennae. Leal and researcher Zain Syed discovered the exact neurons on the antennae that detect DEET, which are located beside other neurons that sense a chemical, 1-octen-3-ol, known to attract mosquitoes.

“I was so delighted when I first encountered the neuron that detects DEET, a synthetic compound,” said Syed. “I couldn’t believe my eyes because it goes against conventional wisdom so I repeated the experiment over and over until we discussed the findings in the lab.”

The UC Davis investigators set up odorless sugar-feeding stations, some containing DEET, and found that DEET actively repelled them. The mosquitoes they used were Culex quinquefasciatus, also known as the Southern house mosquito. The mosquito transmits West Nile virus, St. Louis encephalitis, and lymphatic filariasis, a disease caused by threadlike parasitic worms.

“Despite the fact DEET is the industry standard mosquito repellent, relatively little is known about how it actually works,” said UC Davis research entomologist William Reisen. “Previous studies have suggested a 'masking' or 'binding' with host emanations. Understanding the mode of action is especially important because DEET is used as the standard against which all other tentative replacement repellents are compared.”

What the study means to consumers

Dr. Jamesina Scott, district manager and research director for Lake County Vector Control, said there are several effective mosquito repellents on the market now – DEET, picaridin, oil of lemon eucalyptus, and IR-3535 – and understanding how DEET works to repel mosquitoes will help researchers to identify other compounds that work similarly to repel mosquitoes.

The Centers for Disease Control Web site (www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnile/RepellentUpdates.htm) has information for consumers about those four repellents, Scott said.

“For consumers, the critical point is that DEET is an effective mosquito repellent,” Scott said. “How DEET works is not as important to the consumer as the fact that it works well and that using a repellent reduces the risk of mosquito bites and mosquito-borne illness.”

The important things that consumers should know, according to Scott, are that:

They should use a mosquito repellent when they are outside, especially at dusk or dawn when mosquitoes are most active;

They should look for mosquito repellents containing DEET, picaridin, oil of lemon eucalyptus or IR3535

They should always follow the label directions when using a mosquito repellent.

{mos_sb_discuss:2}