“… we are children equally of the earth and the sky.” – Carl Sagan

In sci-fi movies, the first stirrings of life happen in a gooey pool of primordial ooze. But new research suggests the action started instead in the stormy skies above.

The idea sprang from research led by University of Arizona's Sarah Hörst. Her team recreated, in the lab, chemical reactions transpiring above Saturn's largest moon, Titan.

“We're finding that the kind of chemistry an atmosphere can do has intriguing implications for life on Earth and elsewhere in the solar system,” said Hörst. “Titan's skies might do some interesting chemistry – manufacture the building blocks of life.”

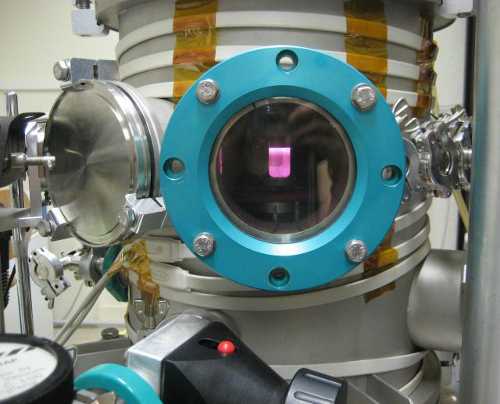

Hörst and her colleagues mixed up a brew of molecules (carbon monoxide(1), molecular nitrogen and methane) found in Titan's atmosphere. Then they zapped the concoction with radio waves – a proxy for the sun's radiation.

What happened next didn't make the scientists shout “it's alive!” but it was intriguing. A rich array of complex molecules emerged, including amino acids and nucleotides.

“Our experiment is the first proof that you can make the precursors for life up in an atmosphere, without any liquid water. This means life's building blocks could form in the air and then rain down from the skies!”

Titan is unique in our solar system. Dotted with lakes and dunes and shrouded in a thick atmosphere of nitrogen and methane, it's a frozen time capsule of early Earth. While the liquid on Titan's surface is methane instead of water, it's the only body in the solar system other than Earth with liquid on its surface.

“We didn't start out to prove we could make 'life' in Titan's skies,” explained Hörst. “We were trying to solve a mystery. The Cassini spacecraft detected large molecules in Titan's atmosphere, and we wanted to find out what they could be.”

In hopes of obtaining clues to the mystery molecules, Hörst used computer codes to search the lab results for matches to known molecular formulas. She decided, on a whim, to look for nucleotides and amino acids.

“When I pressed the enter key, I expected a big 'nope, not there.'”

She left for a break, and got a big surprise upon returning.

“The computer was printing out such long lists I thought I must have made a mistake!”

But there was no mistake.

“We had about 5,000 molecules containing the right stuff: carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen and oxygen. We knew we had the elements for organic molecules, but we couldn't tell how they were arranged. It's kind of like Legos – the more there are, the more possible structures can be made. And they can be put together in many different ways.”

Among the structures identified in the lab experiment so far are five nucleotides found in DNA and RNA, and two amino acids. But she says there could be more amino acids in the mix.

How could Titan's atmosphere generate them?